What's That Gunk in My Newborn's Eye?

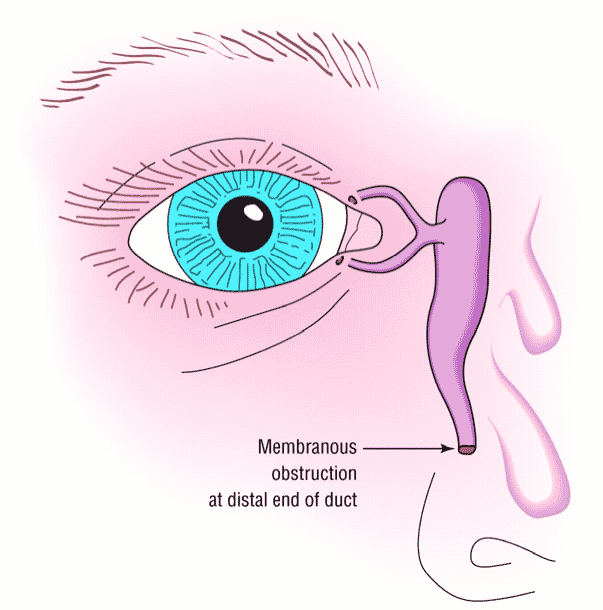

Gunk...not exactly a medical term, but a descriptive one nonetheless. Any parents out there reading this are probably familiar with the following scenario. After the trauma of childbirth (for mom, that is), you feel so blessed to hold your child close and the first thing you do is make sure everything on him/her is perfect. Then, a day or two later, you may notice that there's a lot of mucus in your infant's eye, maybe even so much to cause it to stick shut. The eye is constantly wet with tears. Is it an infection? Do you need antibiotics? What I described is a blocked tear duct, or ophthalmologists refer to it as a neonatal lacrimal duct obstruction (NLDO). All three of my children suffered from this and interestingly, all in the left eye as well. Nikhil is now 2.5 years old and his is much better, but Taj's is actually pretty bad. The good news is that it isn't an infection and it isn't contagious. There are some things that parents can do to help improve matters and lessen the tearing. I wanted to post on this topic since Taj currently has this and I have been treating him at home. Just yesterday, my husband, Dr. Jeff Wong, turned to me and asked "How do you do the massage thing again?" And I thought, if he (a well trained ophthalmologist) can't remember how to do the massage, then, for sure my patients' parents may be forgetting as well.First, what is a blocked tear duct?The tears are constantly manufactured by glands within the eyelids. After lubricating the eye, the tears normally drain into two small holes ("puncta") located on the inner corner of the upper and lower eyelids. Look in the mirror and you can find these puncta on your own eyelids. From there, the tears drain into the back of the nose via the tear duct (a.k.a. nasolacrimal duct). This is why we tend to have a runny nose when we cry! Infants with a nasolacrimal duct obstruction typically have a blockage at the most distant end of the duct immediately before it empties into the nose

What I described is a blocked tear duct, or ophthalmologists refer to it as a neonatal lacrimal duct obstruction (NLDO). All three of my children suffered from this and interestingly, all in the left eye as well. Nikhil is now 2.5 years old and his is much better, but Taj's is actually pretty bad. The good news is that it isn't an infection and it isn't contagious. There are some things that parents can do to help improve matters and lessen the tearing. I wanted to post on this topic since Taj currently has this and I have been treating him at home. Just yesterday, my husband, Dr. Jeff Wong, turned to me and asked "How do you do the massage thing again?" And I thought, if he (a well trained ophthalmologist) can't remember how to do the massage, then, for sure my patients' parents may be forgetting as well.First, what is a blocked tear duct?The tears are constantly manufactured by glands within the eyelids. After lubricating the eye, the tears normally drain into two small holes ("puncta") located on the inner corner of the upper and lower eyelids. Look in the mirror and you can find these puncta on your own eyelids. From there, the tears drain into the back of the nose via the tear duct (a.k.a. nasolacrimal duct). This is why we tend to have a runny nose when we cry! Infants with a nasolacrimal duct obstruction typically have a blockage at the most distant end of the duct immediately before it empties into the nose Approximately six percent of all infants are born with a nasolacrimal duct obstruction (tear duct blockage) affecting one or both eyes. Fortunately, the good news is that at least 90% of these obstructions will clear without treatment within the first year of life.What are the signs of a blocked tear duct?As the tears have nowhere to drain, they will well up on the surface of the eye and often overflow onto the eyelashes, lids and cheek. Normally there are bacteria in the tears and now these have nowhere to drain when a blockage is present. These bacteria tend to grow within the tear duct and cause a pus-like discharge from the inner corner of the eye and on the lashes — frequently observed when the child awakens.It is important that see your pediatrician or pediatric ophthalmologist for a correct diagnosis. There are other serious and vision threatening conditions which can cause tearing in a newborn, and those need to be ruled out.

Approximately six percent of all infants are born with a nasolacrimal duct obstruction (tear duct blockage) affecting one or both eyes. Fortunately, the good news is that at least 90% of these obstructions will clear without treatment within the first year of life.What are the signs of a blocked tear duct?As the tears have nowhere to drain, they will well up on the surface of the eye and often overflow onto the eyelashes, lids and cheek. Normally there are bacteria in the tears and now these have nowhere to drain when a blockage is present. These bacteria tend to grow within the tear duct and cause a pus-like discharge from the inner corner of the eye and on the lashes — frequently observed when the child awakens.It is important that see your pediatrician or pediatric ophthalmologist for a correct diagnosis. There are other serious and vision threatening conditions which can cause tearing in a newborn, and those need to be ruled out.  .Here's picture of my second son. See the yellow crusting mucous in the corner of his left eye and on his eyelashes causing them to stick together? Even though it looks troubling, it doesn't bother him one bit, which is very normal.So, what can be done? Since these obstructions resolve by the time the baby is 12 months old, I manage the condition very conservatively. I typically recommend the following:

.Here's picture of my second son. See the yellow crusting mucous in the corner of his left eye and on his eyelashes causing them to stick together? Even though it looks troubling, it doesn't bother him one bit, which is very normal.So, what can be done? Since these obstructions resolve by the time the baby is 12 months old, I manage the condition very conservatively. I typically recommend the following:

- Crigler massage (see video down below). This is basically massage of the tear duct to get it to open up and create a patent system for the tears to flow. To perform the massage, use your index finger in the corner of the eye, right below the eye and roll the finger downwards over the bony ridge towards the nose. This has been proven to work. Success rates in published studies range anywhere from 30-90%. Do this three times a day. It's easy, free and doesn't harm the baby, isn't that the best treatment? You can see in the video, sometimes it's tricky performing the massage in an infant (in my case, Taj always seems to think my finger is more food for him). Usually I will use my other hand to stabilize his face, but for the video, it was getting in the way of the shot of Taj's face, so that's why he's moving around so much.

- Warm compresses

- Antibiotic drops - these will need to be administered by your pediatric ophthalmologist if there is a lot of green-pus discharge. I typically recommend erythromycin ointment and it's what I've been using intermittently on Taj

- Breastmilk - This is not a medical recommendation, and I'm going to preface this. A lot of old folklore, Ayurvedic medicine and maybe even your Hawaiian auntie down the street has recommended breastmilk for everything. Breastmilk has a lot of wonderful properties, one of which is that it contains IgA, a type of antibody. The theory is that squirted into the eye, the breastmilk prevents the adhesion of bacteria to the eye and decreases the discharge. I only found one published study as to the effectiveness of breastmilk and because the journal was a bit obscure (Journal of Pediatric Tropical Medicine), I wasn't able to read the full article to evaluate it. However, I will say that one of the pediatricians who routinely refers to me was always recommending this to her patients and I thought this weird. Yes, I know my background is Indian and I should be down with the Indian home remedies, but I usually require hard published data before I change my practice style. But, Taj's eye was pretty bad. The antibiotic ointment wasn't doing too much, so I figured, why not give the breastmilk a try. And, I have to admit, it really improved things for Taj. The swelling and amount of discharge lessened considerably.

- Probing and irrigation. This is surgery. I pass tiny smooth wire probes through the tear duct and into the nose, in order to open up the passageway. For adults, we can do this procedure in the office, but obviously a baby is not going to stay still for you to insert long thin metal probes in the eyelids, so this must be done in the operating room under general anesthesia. It only takes about 5 minutes and usually cures the condition. I only do this surgery if the baby is older than 12 months because as I mentioned earlier, 90% of the time, the blockage will clear itself so why put your child through the risk of general anesthesia if not necessary? That being said, this is probably one of the most common procedures that pediatric ophthalmologists perform. It's very safe and effective. There are no incisions or scarring from this operation and there is no significant post-operative discomfort. Just see here for a post by a patient's mother about the procedure.

Here is what the probes look like. I start out using the tiniest diameter probe (on the left hand side) and then increase the size, confirming that I've opened up the passageway. Sometimes, I may also insert a little balloon catheter to open up the passageway. This takes the place of using a silicone tube. When the balloon is used, then no tube is necessary. Though the tube is extremely small and pliable, children do not feel it at all. However, the tube will need to be removed 3-6 months later.So, if your child is like mine - a newborn diagnosed with a lacrimal duct obstruction, don't worry, 9 times out of 10, this will get better all on its own. It resolved with all of my kids but, if it doesn't, the surgery is minimally invasive and painless..